The places probably hit the hardest by the first wave of the Covid-19-pandemic, have been retirement and nursing homes. In Britain, the USA and Germany, for example, between a fifth and a staggering 60% (depending on various counting methodologies adopted) of all Covid-related deaths have occurred in such institutions, despite accounting for a much smaller share of the overall number of Covid-infected individuals.

In Belgium, several nursing homes called for the help of units of Doctors without Borders, who are normally deployed for disaster relief in developing countries. The pre-existing medical conditions of the patients together with the insufficient sanitary measures and the spatial density within these institutions have commonly been identified as the main reasons for this dire statistic. In Italy, the Milanese Albergo Pio Trivulzio made national news repeatedly during the crisis and became the symbol of this devastating situation and of the suffering of the elderly inside retirement and nursing homes more broadly.

The directors of the Trivulzio are now accused of transporting infectious patients to other facilities without safety measures, of failing to procure protective gear for patients and staff, as well as of the intentional concealment of pandemic-related fatalities in order to downplay the massive outbreak inside the institution. As much as we might feel that this nexus of political and financial controversies surrounding healthcare and nursing institutions and their public management is a quintessentially modern phenomenon, it has intriguing historical precedents. After all, the Trivulzio retirement home dates back to the 18th century when it was first established as a pious non-profit foundation for the elderly.

Providing relief to poverty, disease, and old age in early modern times

Very much like today, the backbone of the urban sanitary infrastructure of the early modern period (c. 1500 to 1800) was non-profit, consisting of private foundations (often de facto governed by the public) in the form of hospitals, which was a term used for care-providing institutions in general. Institutions then were generally less functionally differentiated than today, so that a ‘hospital’ could provide simultaneously short-term medical care, distribute alms to the poor and serve as a retirement home with its own resident population.

The sources of revenue of these hospitals were equally diversified, especially if they were foundations relying on their own endowment. Hospitals could run a massive agricultural business based on their landed estates, for example, or collect interest for banking services to clients big and small. Due to the abysmal extent of urban poverty and the all too porous social safety nets, early modern hospitals constantly faced a demand for welfare that exceeded their capabilities by far. Many people in need were left to struggle with the resources they could provide by themselves, such as the support of family and friends or even begging on the streets. In these conditions, the institutions always had to square the circle, so to say, of staying faithful to their charitable mission while at the same time keeping their budgets balanced and safeguarding their patrimony over the centuries of their existence.

Early modern retirement homes

This constant financial pressure would slowly transform the welfare provision of early modern hospitals, especially in their function as retirement homes. Many institutions went on to charge the elderly for food, clothing and accommodation. The pricing should be understood as a compromise between covering costs and the charitable imperative put down in the hospitals’ founding charters. Whereas today medical bills and costs for individual long-term care render retirement homes expensive for insurers and families, early modern contemporaries were luckier in this regard: medical treatments were still too rudimentary to be very costly and labor for care generally quite cheap. Providing food and shelter for the elderly was the essential cost factor involved.

The financial structure for these provisions was particular, however: often the elderly would make a one-time payment to the institution upon admission, which was to cover all services and food until their death no matter when that would be. Whether this deal would result in a loss for the hospital depended largely on how long the retiree would live after retirement. The risk baked into this deal was obvious: for much of the early modern period there was no way of knowing how long people on average would live. Even when the first data on the average human life expectancy were collected in the late 17th century and a mathematical procedure to arrive at average live expectancies in a given population was developed shortly later, this knowledge hardly ever reached practitioners on the ground. Thus, it was easy for a hospital director to succumb to the allure of selling spots at the institution for quick money, under the expectation that the repayment in bread and board would be made in the future by his successors. ‘Pensions’ sold decades ago to long-lived retirees could continue to cost the institution dearly.

Epidemics and the advantage of premature death

Here is where epidemics enter the stage. Like today, the spatial density of vulnerable individuals made hospitals hotspots of contagion, a fact of which early modern contemporaries were well aware. Cynically, the financial structure of the transaction put the premature death of the retirees, at least in theory, in the interest of the care-providing institution. An outbreak of whatever infectious disease could rid the hospital of numerous claimants within days and the emptied spots could be resold, relieving the burdened budget. At the same time, hospitals were, as welfare institutions, called to provide support to a community torn by human loss. This could lead to a profound conflict of interests for hospitals. On the one hand, the aftermath of an epidemics was a rare chance for them to restructure their finances by raising entrance payments for new retirees. On the other hand, this was the very moment when the urban communities needed affordable help the most. Notwithstanding the differences through time, epidemics back then and now forced health care officials to strike uneasy and always imperfect compromises between care provision and budget constraints.

St. Catherine’s hospital in the plague year of 1713

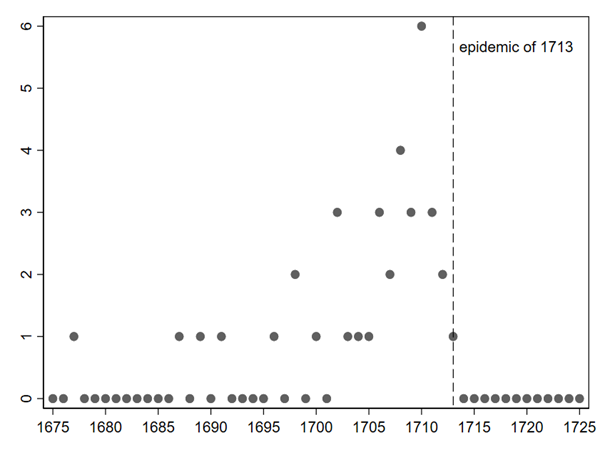

Sitting at the northernmost tip of river Danube, St. Catherine’s Hospital in South German Regensburg was an urban care-providing institution which housed a large number of retirees. In 1713, the city was hit by what historians have -somewhat clumsily- named the “Great Northern War plague outbreak” after a long war in the Baltics which had facilitated the spread of the disease. This was one of the last major outbreaks of plague in European history, and during it a third of Regensburg’s inhabitants perished. St. Catherine’s Hospital was far from spared after the pernicious bacteria had crept inside its walls by September 1713. Amid dying and suffering, the most ordinary procedures were halted. The hospital officials scrambled to keep up with the emergency and ceased to record the deaths of their retirees.

Given that retirees lived on site, their traces in the administrative records of the hospital were manifold. So called ‘Pfrundbücher’ contained the yearly admissions of retirees, some of their personal information, as well as records of their deaths. Day-to-day life within the institution was captured by Haus- and Ratsprotocolle (house and council protocolls), in which the directors and the steering council of the hospital noted small events or decisions they had made. But the many elderly who had retired in the years preceding the plague of 1713 simply “vanished” from the records. Amid the chaos of the pandemic, the hospital’s meticulous record-keeping fell into disarray. We know nothing about the fate of these people but in all likelihood, they fell victim to the disease. This strange presence of both feverish attempts to contain the epidemic, taking place in the city and the hospital, as well as the halting of normal life and everyday activities, such as book-keeping, likens epidemics of the past to those of today.

Should historians in a century’s time look back at the spring of 2020, they will see the same pattern. They will marvel at the hectic bundling of all political and social forces to limit contagion, while noting the gaping holes in our calendars, intended to be filled by sports events, restaurant dinners or academic conferences that never took place. In every period of human history, the most emblematic traces that any epidemic leaves behind for historians to examine are perhaps the gaps: the ceasing of social life, the missing sources, the lives lost.

The intricacies of restarting

It is hard to say how many retirees passed away at St. Catherine’s hospital during the plague outbreak of 1713. Thirty is a likely number. This figure would represent a mortality rate within the institution of roughly 50%, a humbling statistic that is, in some cases, surprisingly close to the estimates advanced for the current Covid-crisis in nursing homes. But, no matter the losses, contemporaries forcefully restarted what had been interrupted by the disease: the year of 1714 saw the arrival of 39 new retirees whose personal reasons for admission might have very well been prompted by the catastrophe. Would the directors seize the chance to raise the prices? They actually settled for a compromise: they did not give discounts due to extraordinary circumstances, but they also did not try to wrestle higher sums from the elderly in order to restructure the budget. The understanding of justice and financial sustainability embedded in the entrance fees had survived the epidemic, at least temporarily. One could argue that this decision backfired. Just one decade later, in the 1720s, the hospital tumbled into a financial crisis. The officials initiated a massive price rise, the effects of which were to last for the remainder of the 18th century. There is, of course, no simple causal explanation for this development, because the hospital possessed various sources of income. However, the fact that the hospital directors had missed the opportunity to put their “retirement business” on a sounder footing during the epidemic might have contributed to it.

Rethinking welfare in a post-pandemic world?

St. Catherine’s Hospital’s experience of the 1713 epidemic was without a question one of unconditional suffering. The breakdown of order and of every routine was so complete that even scribbling the name of a deceased and a date of death was already beyond what was possible. But while the graves of many dead were still fresh, the decision makers faced the question of how they would respond and adapt to their changed circumstances. This epidemic was not just an event that was suffered by those who experienced it. It also opened a space for decision-making in a new post-epidemic social reality that gave contemporaries the rare opportunity to redesign their environment. For the hospital directors, this could have taken the form of rethinking the ideas of individual charitable deservedness and institutional financial sustainability.

In other words, they might have reconsidered the function of public welfare in times of crisis. Instead, they chose to face the half-empty hospital and a devastated community with a pricing policy that was remarkably unresponsive to the gravity of change all around them. Arguably, by doing so they failed to aim at either of their policy goals, neither widening access to retirement much nor decisively relieving the budget. Perhaps the story of St. Catherine’s Hospital reminds us that deadly epidemics do not automatically lead to profound social change, neither in 1713/14 nor in 2020. Instead, they can also function as a trigger for a universally human propensity to cling to the time-proven practices under the promise of continuity after an unsettling social disruption. In any post-pandemic world, the continuation of the past is as much a decision as it is to break with it.

Contributor

Ludwig Pelzl is a doctoral researcher in the Department of History and Civilization at the European University Institute. Ludwig’s interests lie in the social and economic history of pre-1800 Europe. After completing his studies in Germany and Sweden, he is now researching a little-known story of urban retirement homes in early modern Europe.

Further Readings

Holt, Alison and Butcher, Ben, “Coronavirus deaths: How big is the epidemic in care homes?” in BBC News Online, 15.5.2020 [retrieved under https://www.bbc.com/news/health-52284281 on 15.7.20].

Kellner, Katharina, Pesthauch Über Regensburg: Seuchenbekämpfung Und Hygiene Im 18. Jahrhundert, Studien Zur Geschichte Des Spital-, Wohlfahrts- Und Gesundheitswesens, Bd. 6 (Regensburg: Friedrich Pustet, 2005).

Neumaier, Rudolph, Pfründner: Die Klientel Des Regensburger St. Katharinenspitals Und Ihr Alltag (1649 Bis 1809), Studien Zur Geschichte Des Spital-, Wohlfahrts- Und Gesundheitswesens, Band 10 (Regensburg: Verlag Friedrich Pustet, 2011).

Neumaier, Rudolph, “Die Pest im St. Katharinenspital,” in Reil, R. ed. Die Pest 1713 in Regenspurg und Statt am Hoff (Regensburg: Manzsche Regensb, 2013).

New York Times, “More Than 40% of U.S. Coronavirus Deaths Are Linked to Nursing Homes,” in New York Times Online, 7.7.20 [retireved under https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-nursing-homes.html on 15.7.20].

Norddeutscher Rundfunk, “Corona: Viele Opfer lebten in Pflegeheimen,” in NDR Online 11.6.2020 [retrieved under https://www.ndr.de/nachrichten/niedersachsen/Corona-Viele-Opfer-lebten-in-Pflegeheimen,corona3416.html on 15.7.20].

Santangelo, Stefano, “Il caso del Pio Albergo Trivulzio sarà il grande scandalo del coronavirus in Italia,” in Rolling Stone Italia Online, 10.4.2020 [retrieved under https://www.rollingstone.it/politica/il-caso-del-pio-albergo-trivulzio-sara-il-grande-scandalo-del-coronavirus-in-italia/511761/ on 15.7.20].

Stevis-Gridneff, Matina et al., “When Covid-19 Hit, Many Elderly Were Left to Die,” New York Times Online, 8.8.20 [retrieved under https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/08/world/europe/coronavirus-nursing-homes-elderly.html on 8.8.20].