Plague in the specific

While researching historical plague during a pandemic has been a strangely soothing experience for me, I’ve been told it has made me rather difficult to talk to. “You keep saying the situation isn’t as bad as the literal Black Death, like that’s a comfort,” a friend said, making it clear that it was not at all a comfort, that she had learned more about the symptoms of bubonic plague than she cared to, and could we perhaps talk about something else?

Though I learned to reign it in while talking to others, the parallels between the current pandemic and past outbreaks of bubonic plague never stopped standing out to me. I kept coming back to one question in particular: how was medical expertise conveyed using print (that is, movable type set in a printing press) in the very early days of that invention? Looking at an early printed plague tract, originally written in Latin in the 14th century, I came across this excellent piece of advice: tempore pestilentia quando fiat ventus meridionalis: manere in domo per totum diem. That is: in times of pestilence, when there is a southerly wind, remain in the house all day. What a sentence to read during a lockdown, when I had no choice but to follow this piece of advice from seven centuries ago – no matter which way the wind was blowing!

Despite certain similarities like this, the current pandemic really is very different from the Black Death, both in terms of how lethal the disease is and in how medical experts react to it. The Great Mortality (magna mortalitas, in the language of the time) that came to Europe in the 14th century was so dangerous, and spread so quickly, that medical experts today still ask themselves how it could be possible. Plague, as a word, strikes a different chord compared to, say, cholera or malaria. You cannot speak of a cholera of locusts, or be malariaed with doubt. Terrible as cholera and malaria might be, they do not carry that rhetorical ring that allows us to use “plague” to mean calamity, or more specifically ruinous outbreak of infectious disease.

And yet there is a disease called plague, which can take bubonic, septicaemic or pneumonic forms. That is, the bacteria Yersinia pestis can attack the lymphatic system (an important part of the immune system), creating a bubo, a swelling of the lymph nodes in the armpits, groin or neck, or it can attack the blood (causing septicaemia, or blood poisoning) or the lungs. The bacteria need not limit itself to causing only one of these, however, so pneumonic plague might well follow on the heels of the other forms. Only three good things can really be said about any form of plague: that, when it kills, it kills relatively quickly, that it is very rare in the world today, and that it can be treated with antibiotics.

For the author of the text I have been investigating these last few months, the one who advised me to stay inside, the plague was neither rare nor easy to treat. When he wrote the Regimen contra pestilentiam (The Rules Against the Plague, as it is known) in the 1370s, there were still people alive in Europe who could remember a time before the plague arrived. Today, we believe it reached Crimea in 1347, passing on to the Mediterranean the next year, moving with astonishing speed. From the Mediterranean, the plague reached Scandinavia in 1348. Unlike many other outbreaks of infectious disease, it did not seem to concentrate in the larger cities, but hit smaller villages and settlements, too. In order to reach those villages, it must have spread by land routes in addition to by sea, in a time when the sea was the highway. In any case, it was ships that were the targets of a practice, started in modern-day Dubronvik in 1377, called the trentino – a 30-day separation period for ships and crews coming from plague-infested areas, before they were allowed to step ashore. As the period was later lengthened to 40 days, the name was changed to quarantino, reflecting the Italian words for thirty (trenta) and forty (quaranta). This is the origin of our quarantine. The practice was then taken up in other ports, Marseille and Venice among them.

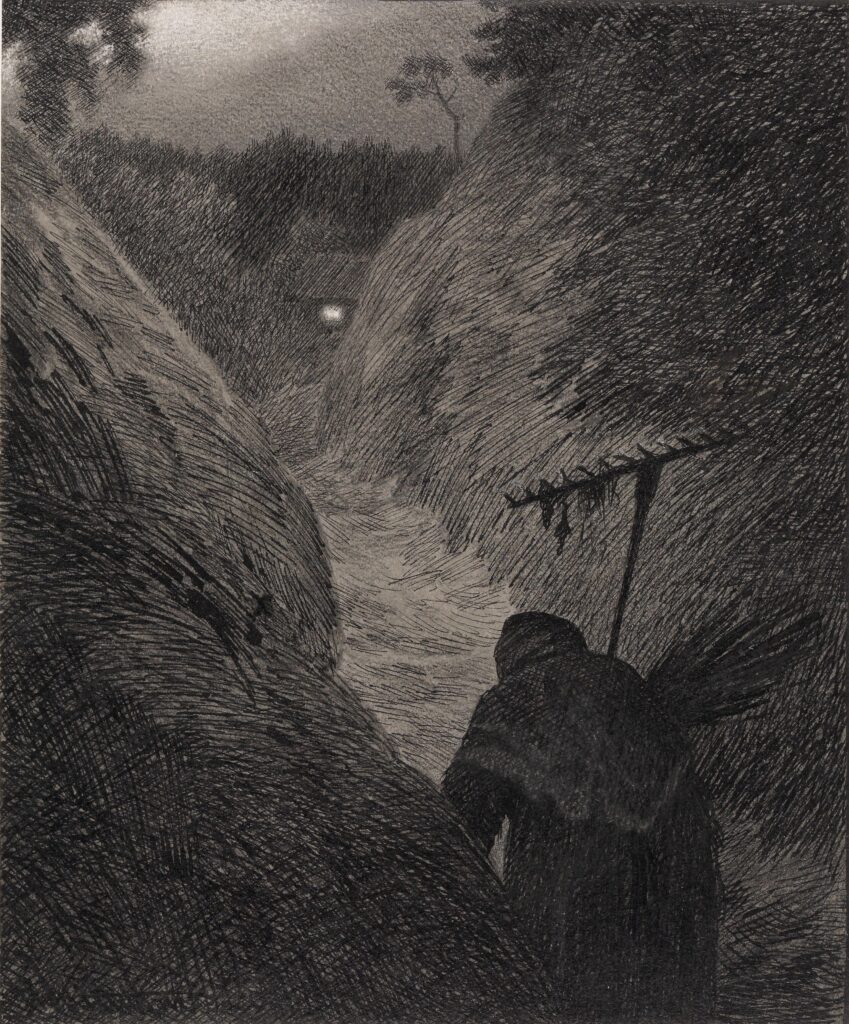

The Norwegian city of Bergen could not have known, in 1349, that they should have practiced this quarantining of ships. Nobody knew. I still remember learning, in school, about the English ship drifting in to port, nothing alive on board but the rats, and the fleas they carried, and the bacteria those fleas, in their turn, carried – a veritable ghost story, accompanied by frightening images of Pesta, a personification of the plague. She takes the form of a crone with a broom and a rake, and when she arrives at a house where every inhabitant must die, she runs the broom before the door, while the rake leaves some behind to survive. This depiction of the plague in person arriving at your door, or drifting in to harbor on a ship of the dead, is more evocative than it is factual. The folk demon herself probably doesn’t date back to the time when the plague first arrived in Scandinavia, and where and when that arrival took place, precisely, is a matter for debate.

Still, these stories contain some real questions and concerns. Ships really were identified as a source of disease, hence the practice of quarantine. And how, people asked themselves, could the disease kill some, but not all of the people in a household? How did the disease spread from place to place? The medical experts of the time had to provide answers.

Plague according to a medieval physician

For Jean Jacme, the author of the text I’ve been researching, this business with the rake and broom would not at all serve as an explanation. He was a somebody; chancellor of the prestigious University of Montpellier, which specialized in medicine, and personal physician to the Pope. He knew Greek and Arabic medical authorities, though probably in Latin translation. Drawing on these, he had to provide an answer to the same question that gave Pesta her broom and her rake: why is it that some people die of plague, and others do not? A learned doctor like Jacme had to understand and explain a disease that moved so quickly experts still struggle to understand how it could have been possible, that can take several different forms with different symptoms, and whose initial outbreak had killed (we now believe) between one third and one half of Europe’s population before becoming a recurrent, lurking threat.

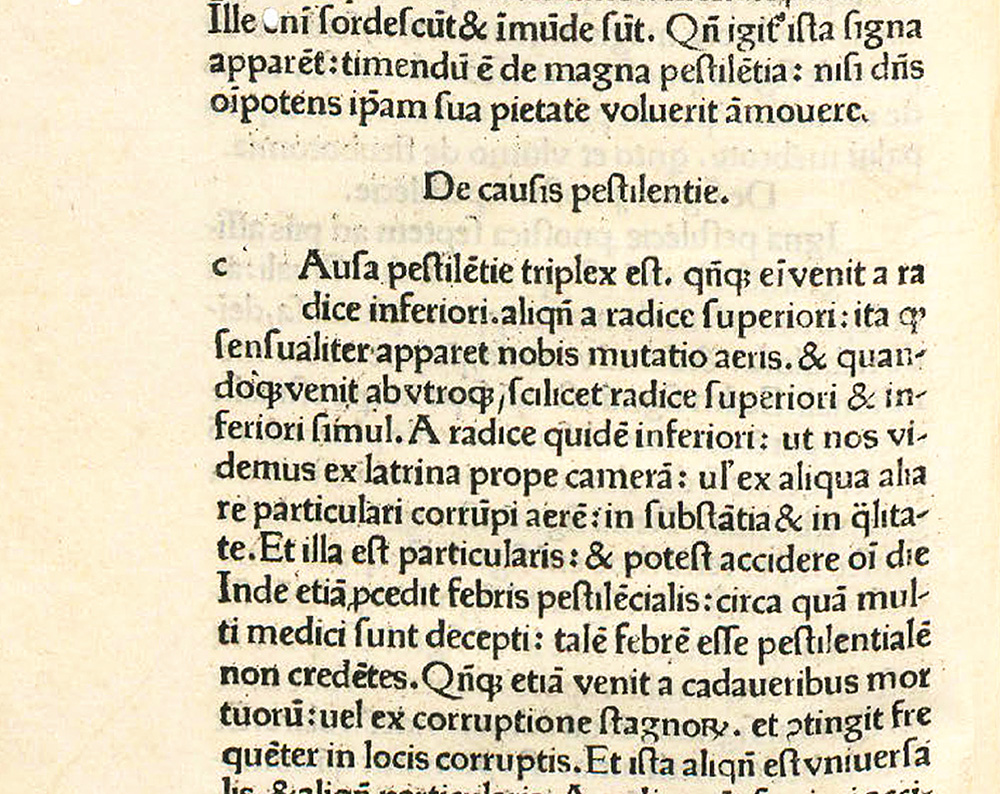

Jacme set out to do this in the text now usually known as the Regimen contra pestilentiam, a short and textbook-like overview of the subject which seeks to explain how to recognize that a plague might be in the offing, what causes plague, how to live in such a way that one is unlikely to catch it, and what to do if, despite precautions, someone does contract plague. The edition I’ve been reading is actually a reworking from a century later, printed in 1480 by one Ulrich Gering in Paris, who for reasons now lost to time attributed the book to a Danish bishop called Kamiti. This bishop does not seem to have existed. Perhaps the printer wanted to add a hint of the exotic, or a certain religious authority, to the book?

Whatever the case might be, before we dive into what Jacme actually wrote, it would be useful to first look at what a learned doctor of medicine was expected to know. He would have gone to university, where he would have learned how to read and write proper Latin before he went on to study medical theory. He would have to become very familiar with the humoral system, which played a key role in European medical thought from antiquity until (to simplify) a cell-based understanding of how the body works took over in the 19th century. In the humoral system, we all have a specific balance of four bodily humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile) which are affected by such things as our mood, our diet, the weather, and of course any medical treatment we might be using. For example, this system describes young men as having a lot of blood, and blood is understood to be both hot and wet. Being blood-dominated, or sanguine, makes them fun to be around; happy and a little impulsive. The learned doctor would be expected to learn about this system through a body of texts from Antiquity and the Islamic Golden Age (around 800-1300), and to find a job advising the rich on how to achieve balanced humors.

First, we note that Jacme considers signs as separate from causes. The first are things to look out for, that might give us an early warning to get out of town before the disease strikes. The main thing in this regard is shifting or unseasonal weather, though the real heavy-duty bad omen is a comet. Quote: “These are the effects of a comet: Death rages. Cities are seized. The sea swells. The sun is covered. Kingdoms fall. The people are tormented with plague and famine” – this passage, which is somewhat dubiously attributed to Aristotle’s Meteorologica, stands out in an otherwise rather measured, teacherly text. Causes, however, are more general. Plague, Jacme tells us, can come from above or below. From above, it comes in the form of the air being infected by the position of the planets. From below, it comes from stagnant water or rotting corpses.

Why the division into signs and causes? The reason is connected to that stack of theoretical texts Jacme had had to learn. For him, a real doctor had more to go on than mere empirical observation. He knew not only the signs of disease, but also the causes. And the causes he outlines, unlucky stars and rot rising from below, will be used to answer the questions that we’ve already raised in this text:

Quote: “But two questions might be asked about [the causes of plague]. The first is why one person should die, and another not, and why in one town or one house people should die, and in others not. The second is: are such pestilential diseases contagious?”

Sometimes, reading historical texts, one wants to reach through the page, grab the author by the neck and tell him what’s what. In case any readers now feel the need to shout at Jacme that yes, you fool, the plague is highly contagious, let me reassure them that he already knows. But first, let us look a little closer at Jacme’s answer to his own rhetorical question. If all the people in a given place are breathing the same infected air, why do some of them die of plague, and not others?

Because, Jacme explains, the influence of planets is different from place to place (as is the number of rotting bodies, presumably, though this goes unmentioned in the text), and because that influence strikes different bodies differently depending on those bodies’ susceptibility. People with hot bodies and open pores are much worse off, he states. There is no further explanation in the Regimen contra pestilentiam of why, exactly, people who run hot and have open pores are at greater risk, so we will have to interpret this for ourselves. Starting from a fairly safe bet, we can consider that the open pores might let the infected air in. More daringly, perhaps Jacme thinks hot-natured people are at higher risk because rot is more likely to occur in a hot, humid environment than a cold, dry one.

That is Jacme’s answer to the question of why some people, but not all, die of plague. What about contagion? At first blush, Jacme’s understanding seems very similar to ours: “And all gatherings or crowds should be avoided, as far as possible, so that one person’s breath does not infect another.” Furthermore, one should wash one’s hands frequently. The University of Montpellier can still stand by their Chancellor of seven centuries ago, as far as this piece of medical advice is concerned! However, we have to be careful not to backdate our own understanding of how contagion works to Jacme. He also says that, as for people who cannot avoid being around infected people and places, “I advise them as far as possible to avoid all things that can cause putrefaction, which principally means avoiding the frequentation of women,” though the wind is also an important concern.

What does this tell us? Leaving aside how exactly sex with women is supposed to cause rot, it tells us that Jacme seems to consider that several sources of rot, of which plague is one, can add up and overwhelm the body. The difference between plague and too much southerly wind is then one of degree, not of kind. Both, though, can be avoided by staying inside, as Jacme advises us to do!

Contributor

Vigdis Andrea Baugstø Evang is a second-year Ph.D. research at the European University Institute, in the Department of History and Civilization. Their research focuses on the history of early European book printing, on the connections between printing and knowledge creation, and on the transmission and spread of scientific concepts through printing.

Further readings

Jacobi, Johannes, Regimen contra pestilentiam (Paris: Ulrich Gering, 1480). https://archive.org/details/4079484/mode/2up.

Cipolla, Carlo M, Cristofano and the Plague (London: Collins, 1973).

Coste. Joël, Répresentations et comportements en temps d’épidemie dans la littérature imprimée de peste (1490-1725) (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2007).

Fabbri, Christiane Nockles, ‘Continuity and Change in Late Medieval Plague Medicine: A Survey of 152 Plague Tracts from 1348 to 1599’ (PhD Dissertation: Yale University, 2006).

Heinrichs, Erik A, Plague, Print and the Reformation. The German Reform of Healing, 1473-1572 (London; New York: Routledge, 2018).

Rand, Kari Anne, ‘The Elusive Canutus: An Investigation into a Medieval Plague Tract’, Leeds Studies in English, New Series 51 (2011): 193-206.

Nutton, Vivian, Pestilential Complexities. Understanding Medieval Plague (London: Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2008).