‘I thought Herr Hofrat would approve of my decision and I am convinced that nobody will be casting another stone at our clinic when they hear that I have voluntarily self-isolated along with the nurses … The condition of one of the nurses is very worrying … and I’m afraid that our suspicion will be confirmed … I leave you with the plea to forgive me for missing another shift (which I have done unhappily and with a heavy heart).’

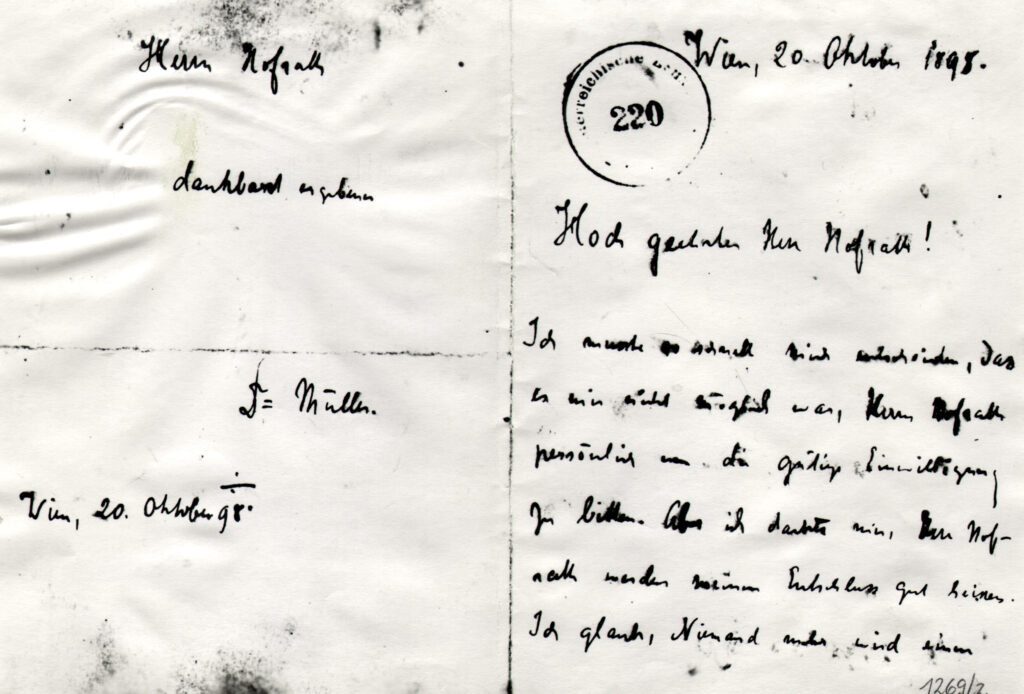

In the winter of 1949, Karl Fellinger, head of Vienna’s Medical Clinic, received a letter from Copenhagen. It contained a crumpled and blotted piece of paper, which he unfolded and read along with the accompanying lines. The message itself was friendly and appreciative, but the old document, dated 20 October 1898 and evidently washed out with disinfectant, told a different story. Its author, a certain Dr. Müller, described a horrible event slowly unfolding around him, and expressed hope that his radical actions might clear the names of those involved. The letter was vague in the details, but Fellinger did not need context. He knew exactly who the author was and what had happened to him; indeed, he passed a statue dedicated to Müller every day on his way to work. Without much hesitation, Fellinger called for someone to have the letter reproduced and later sent the copy to the Institute for the History of Medicine. The original he kept, framed it and put it up on his office wall, to serve as a constant reminder of the events that shook Vienna half a century before.

Since the middle of the 19th century, a largely underreported outbreak of the plague had affected China, but in 1894, when the plague broke out in the major trading hub of Hong Kong, western scientists took note. Yersin and Kitasano, associated with the two leading laboratories at the time, the Institut Pasteur in Paris and the Prussian Institute for Infectious diseases directed by Robert Koch, travelled to Hong Kong and quickly and for the first time identified the bacillus responsible. While their major scientific achievement was feted around the world, the plague continued to spread, first to the north of India and then to the south, reaching the city then called Bombay (todays Mumbai) in 1896. The consequences were terrifying. Panic spread as bodies were piling up in the street and the colonial authorities failed to control the situation. The ever more brutal attempts to stamp out the disease lead to riots, attacks on hospitals, and a mass exodus from Bombay the beautiful, as the colonial overlords had been fond of calling the now desolate city.

In Europe, this new outbreak caused consternation and intrigue in equal measure, as several countries decided to send missions to study the situation in Bombay and the way this old but still unknown disease spread and killed. Russia, sharing a large border with India, would send a group of scientists from Kyiv. In Germany, Robert Koch’s centre prepared an exploratory corps, but was slowed down by the fact that Koch himself was occupied with research in East-Africa. Yet surprisingly, the earliest mission to start their way to India was an outfit from the Austro-Hungarian academy of Sciences. A young group of researchers, led by Hermann Franz Müller, had volunteered to travel to Bombay, tasked with researching the plague from an etiological, anatomical-pathological, and clinical perspective. They were also accompanied by a young doctor, Rudolph Pöch, who had made a name for himself as an early X-Rays pioneer and an expert photographer. It would be his task to document their travels and research.

On the 3rd of February 1897, the majestically named “Imperator”, a ship operated by the Austrian Lloyd, left Trieste for Bombay. Cramped with material for clinical examinations and what amounted to a mobile laboratory, it had virtually no travelers on board. Fear of the Indian outbreak had spread in Europe and only three passengers had boarded with the young research team, which enjoyed a first-class-trip free-of-charge. After more than two weeks, which included a crossing of the Suez Canal that Pöch immortalized as one of the earliest photographs of the trip, they landed and contacted the local authorities. After an invariably drawn-out exchange of pleasantries, they were put in touch with a Parsee doctor by the name of Choksy, a local expert showed them their new workplace, a crowded hospital that he was in charge of, situated in the south of the city on Arthur Road.

Austria-Hungary had no colonial possessions outside of Europe and the work in Bombay opened new perspectives for the young doctors. Their reports to the Academy of Sciences show them grappling with their new surroundings and trying to comprehensibly relay their complex social interactions to Vienna. To communicate with patients, whose names they found phonetically written on their respective beds, they asked for the help of nurses and other intermediaries. For a more general appreciation of their surroundings, including explanations of religious beliefs and caste-systems, they relied on colonial information, sometimes adding personal experiences to confirm or question existing stereotypes.

Outside of the hospital, a small hut was assigned to the Viennese team to serve as a dissection place. The practice itself was problematic and caused frequent discussions and altercations in Bombay, and the team was aware of the often-negative reputation the hospital had amongst the population. Yet, in their reports, they seemed more distressed by their inability to trace the patients from the ward, where Müller undertook clinical examinations, to the dissection hut, where other members of the team were working in the afternoon. The dissection room itself was well lit but crowded with invited and uninvited visitors alike causing nearly unbearable temperatures. The tables were unstable and dripping with blood and mercury chloride, which the Austrian team used to such excess that at least one of them later showed signs of poisoning. Nevertheless, despite the gruesome conditions, none of them fell gravely ill, while the epidemic raged around them.

After less than two months, the situation started to improve. Cases declined and the opening of various other hospitals meant patients would now be spread more widely within the city, where other missions were still trying to assemble more of what they called “material”. The Austrians however, having had collected samples and an impressive number of medical histories, decided to leave on the next possible crossing of the “Imperator” on the 1 of June. Sailing under quarantine flag, nursing mild plague symptoms and poisoning from the disinfectant, their descriptions of the return journey seem much less pleasant than the outgoing trip. They were enthusiastically welcomed in Trieste, but not given much time to recover. Most of the team had to return to their habitual work almost immediately, leaving them with few opportunities to continue their research on the plague.

At the old general hospital, a small room had nonetheless been allocated for their laboratory work, where they could also rely on the help of an assistant named Barisch. Over the next few months, Barisch and some members of the original team would conduct experiments on well over 700 animals, which they kept in small cages inside the laboratory. Everything seemed to be going well until Barisch fell ill with a high fever. Ghon, a member of the Bombay team, was called to examine him. Barisch’s wife explained that he had been out drinking all night a couple of days ago, had arrived home freezing and not been feeling well since then. Ghon, although suspicious, diagnosed influenza, but also took a sample of Barisch’s sputum for further tests. The patient’s condition, however, did not improve and the next day the expedition leader, Müller, had to be consulted. He diagnosed Barisch with pneumonia and seemed very relaxed about the whole state of affairs. Ghon however had grown increasingly nervous and insisted on Barisch’s immediate isolation.

The young assistant was now brought to a so-called isolation room a couple of hundred yards away at the Clinic for Internal medicine, where Müller worked as an associate professor. Epidemiologically, the room was a disaster, being situated between two large patient halls and not allowing for easy ventilation. The situation was aggravated by the fact that Barisch was not really isolated at all. Two nurses – one of them only a trainee – were assigned to his care and the Clinic’s head, Prof. Nothnagel himself, came to visit and examine the laboratory assistant. Shortly afterwards, Barisch passed away and on the same day Ghon found in his sputum what he had dreaded: the same bacillus that he had seen so often in Bombay – yersinia pestis. Yet despite the many critical press reports that followed, many in Vienna’s medical establishment thought that the situation, as dreadful as it had been, was now over and that further damage had been avoided.

Two days later, however, the trainee nurse, Albine Pecha, fell ill. Now all hell broke loose. On official orders both of the nurses were transported to the quarantine area of a newly built hospital specialized in infectious diseases. Müller, who had been cleaning up the laboratory in the previous days accompanied them voluntarily. Panic now spread in Vienna and the press began a series of near-hourly reports on Pecha’s fever and pulse, increasingly interspersed with sensationalist backstories of her life.

‘She was the most beautiful of her sisters and had several suitors from the time she arrived in Vienna, but her reputation remained impeccable (…) last spring she was working as a maid in one of the best hotels in Karlsbad. An ailing Irishman stayed in this hotel, who engaged her as a nurse, but asked her to undertake professional training first. So she was sent to Vienna, on account of her future employer.’

Stories, however, were not enough. A newspaper artist would later come to sketch her in her cell – albeit from a distance – and small portrait-postcards bearing her image sold in the thousands during the following days.

On the 20 of October, Müller, who – ever the scientist – had been taking notes on the development of Pechas illness, started to feel unwell himself. It was quickly confirmed that he too suffered from the plague. Yet help it seemed, was on the way. A dispatch from France arrived, containing anti-plague serum personally delivered by one of Pasteur’s assistants, a Viennese doctor who allegedly boarded the Orient-express from Paris in such a hurry that he only took the medication and an umbrella with him. The serum was administered to everyone in quarantine apart from Müller, who steadfastly refused – claiming that nothing could save him. While Pecha was fighting for her life, sustained by ever-increasing doses of serum for another week, Müller passed away the following day. The room along with his clothes and writing materials were drenched in carbolic acid and later given to his family, along with a last letter to his superior Hermann Nothnagel – which would return to Müller’s place of work half a century later.

There was an instant outpouring of sympathy for the young victims of the plague, in the aftermath of these events, but while both were interred in dedicated tombs, only Müller would receive more lasting honours. In accordance with 19th century ideals, his refusal to take medication and his decision to self-isolate were widely interpreted as heroic gestures and a hastily drawn-up committee paid for a statue directly comparing him to a hero of ancient Roman folklore. While the young girl and her dreams – so vividly described in the press while she was alive – are as forgotten as the laboratory assistant Barisch, Müller’s statue still stands in a courtyard of the old hospital. Without a plaque to commemorate the thousands the plague killed the same year all over the world or his colleagues that died in Vienna, it serves as a curious reminder of the fickleness of public memory.

Contributor

Dr Jakob Lehne was born in Vienna and educated at King’s College London, the London School of Economics and Humboldt University Berlin. In 2015, he finished his PhD in history at the European University Institute, Florence. He is currently working as a researcher and curator at the Collections of the Medical University of Vienna, where he studies history of medicine, in particularly the history of epidemics and gynaecology.

Further reading

Catanach, Ian J. ‘Plague and the tensions of empire: India, 1896–1918’, in Imperial medicine and indigenous societies. Manchester University Press, 2017.

Flamm, Heinz. “Die österreichische Pestkommission in Bombay 1897 und die letzten Pest-Todesfälle in Wien 1898.” Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift 168.15 (2018): 375-383.

Kidambi, Prashant. “‘An infection of locality’: plague, pythogenesis and the poor in Bombay, c. 1896-1905.” Urban History (2004): 249-267.

Teschler, Maria. “Die Wiener Pest-Expedition 1897 – Rudolf Pöchs erste Forschungsreise.” Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 136/137 (2006/07): 75-105.